White Burgundy Wine: A Collectors Guide

November 30, 2019

Discover the allure of White Burgundy wine: A Collector's Guide. Uncover finest vintages, terroirs & techniques. Elevate your collection & tasting experience

Few fine wines in the world share the seductive elegance and price of Pinot Noir made in its spiritual homeland of Burgundy.

At its best, as Pinot fan Alex Hunt MW once succinctly said:

“Pinot Noir fuses wild beauty with graceful control.“

Discover more about France’s Wine Classifications

Whatever the appeal of Burgundy wines, be it the prohibitively expensive finesse of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay from the Côte d’Or and Chablis, or the more affordable and in vogue Burgundy alternatives of Aligoté and Gamay in Beaujolais, classification is key to understanding the region’s lauded wines.

After all, understanding the region can be a tall order for consumers and buyers who need to familiarise themselves with dozens of names of producers who generally operate not only small plots of vineyards but, in some cases, the most minutely divided-up, tiny plots of vines in the world.

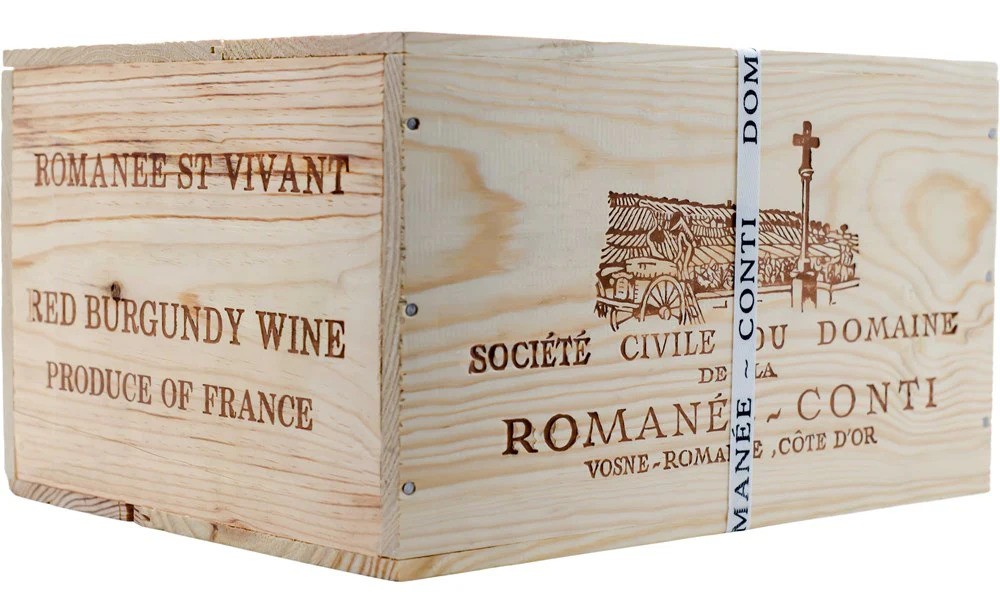

Known as the smallest AOC (PDO) appellation in France, La Romanée Grand Cru vineyard, for example, is just 0.8 hectares in size and produces around 4,000 bottles per year – the wine sells at an average price of $7,105 a bottle. Unlike its arch-rival Bordeaux, Burgundy historically did not receive an investment of outside capital to fund large Chateaux.

Home to the production of some of the world’s most sought-after wines -across a vineyard area of under 30,000 ha – just shy of 4% of the total vineyard area of France – means the land is extremely expensive. In contrast to Bordeaux’s estate-based classification, Burgundy’s wine classification is based on the terroir of its vineyards and the potential of each site.

Wine has been made in the Burgundy region for more than 2,000 years, well before the region became part of France; that’s before the arrival of the Romans and, later, the Franks (a Germanic tribe that eventually gave rise to the French identity), who defeated the Burgundians in battle in the year 536AD. Following the French Revolution, vineyards, once owned by the Church or the nobility, were sold off in 1791, with vine plots divided between several owners. And crucially, even today, Napoleon shapes Burgundy vineyards with laws dating back to 1804 that are still in force.

This Napoleonic code dictates not only that each family member must receive an equal inheritance but also that each item of inheritance must be split equally; for example, if four children inherit four vineyards, each vineyard must be divided into four instead of each vineyard going to one sibling, Burgundy wine expert, Jasper Morris MW, has explained. That may be cumbersome and problematic. Yet, a hectare of vineyard of Grand Cru vineyards can cost more than €10million; in September 2024, Luxury goods giant LVMH paid €15.5 million for the 1.3 ha Grands Crus vineyards of Domaine Poisot in Burgundy’s Côte d’Or.

Under the impetus of the Benedictine and Cistercian monastic orders and the Valois Dukes of Burgundy in the Middle Ages, Burgundy communities demonstrated their ability to identify, exploit, and progressively distinguish the geological, hydrological, atmospheric, and pedological properties and productive potential of small vineyard plots known as Climats.

Cistercian monks, an order founded in 1098 and recognized as the first producers of Chablis, are believed to have pioneered both the classification system and the concept of terroir. Having expanded ownership of vineyards, Cistercian monks experimented, recorded, and compared growing data showing how different vine plots produced different wines. Essentially, they were able in the 12 and 13th centuries to acknowledge different ‘Crus’ or growths, laying the foundation for classification.

The Duchy of Burgundy governed Burgundy from 1363 to 1477, during which the region became known for producing Europe’s finest wines, with wine as its leading export product. Claude Arnoux’s Dissertation on the ‘Situation of Burgundy,’ published in 1728, became the first major work on burgundy wine. It centered on the famed red Pinot Noir wines of the Cotes de Nuit and the renowned Oeil-de-Perdrix (Partridge-eye) pink wines of Volnay.

In 1855, Dr Jule Lavalle published the first informal classification of the best vineyards in Burgundy, the same year as Bordeaux’s 1885 classification. His work, ‘History and Statistics of the Côte d’Or,’ became formalized in 1861 when the Beaune Committee of Agriculture, in consultation with Dr Lavalle, devised three classes of vineyards; most of the first-class vineyards would eventually become Grands Crus with the adoption of France’s AOC appellation system in the 1930s.

Burgundy, Europe’s most northernly fine wine region for still wine production, covers five winegrowing regions: from Chablis (in the north, in the Yonne) to the Mâconnais in the south, on the Beaujolais border, via Châtillonnais (Châtillon-sur-Seine), Côte de Nuits(from Dijon to Corgolin), Côtede Beaune (from Ladoix-Serrigny to Santenay) and Côte Chalonnaise (from Bouzeron to Saint-Gengoux-le-National). All these wines can claim the Burgundy appellation, but their classification is much more structured and reflects, in principle, the quality of the wines.

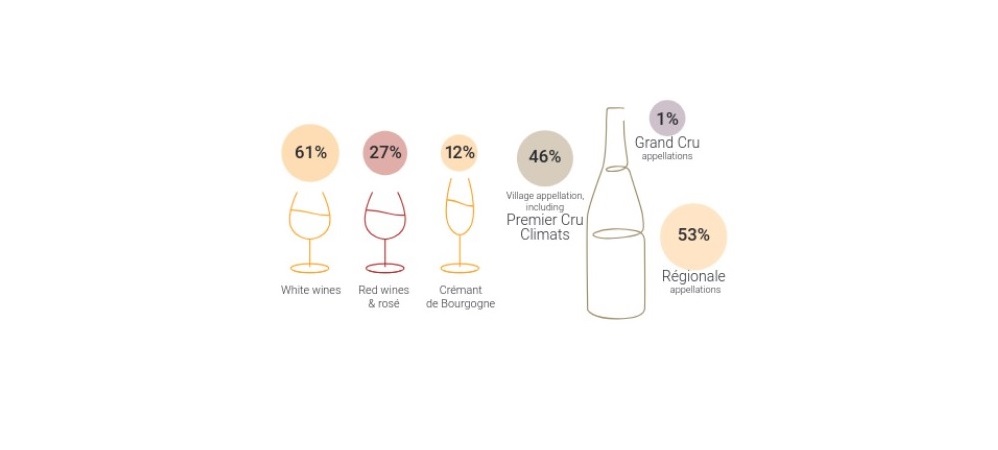

Grand Cru (1-2% of production): The Grand Crus are at the top of the quality pyramid (barely 2% of the winegrowing area). Burgundy officially has 33, 1 in Chablis, 24 in Cote de Nuits, and 8 in Côte de Beaune. These wines are at the highest and most prestigious level, featuring Burgundy’s best plots with their own designated appellations. These red and white wines are known for their exceptional quality and aging potential and are made from vineyards with characteristics that go beyond the typicality of their village.

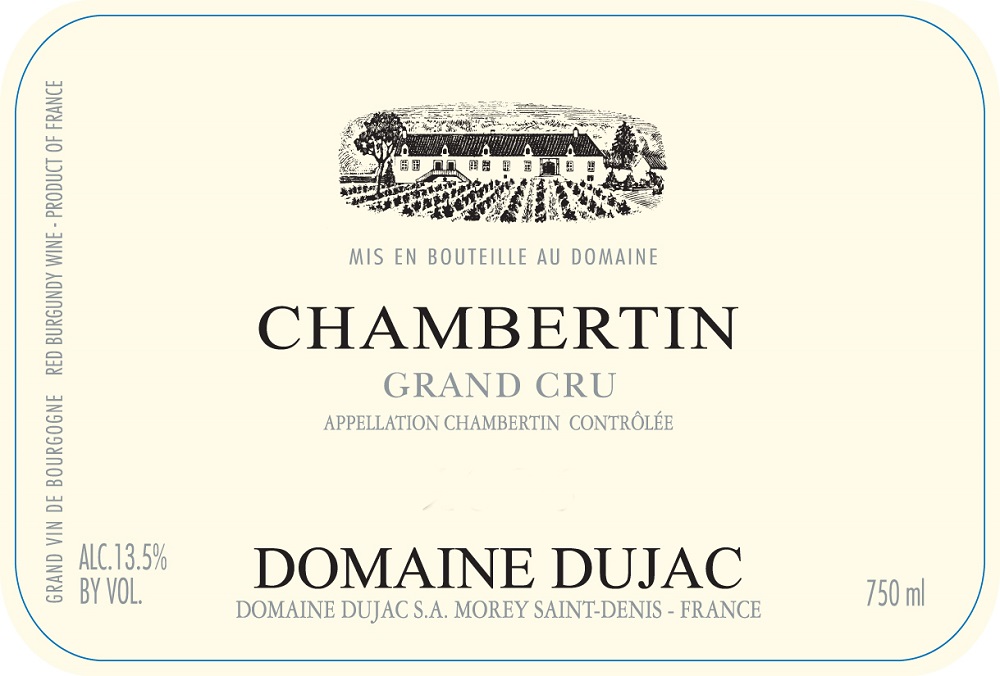

Red Grands Crus are mostly found in the Côtes de Nuits villages of Gevrey Chambertin, Morey St Denis, Chambolle-Musigny, Vougeot, Flagey-Echezeaux and Vosne-Romanée. Among the best-known red Grands Crus are Romanée-Conti, La Romanée, La Tache, Clos de Vougeot, Richebourg, La Grande Rue, Mazis-Chambertin, Clos de Tart, Close St Denis, Clos de la Roche, and Close de Vougeot.

These red and white wines showcase exceptional quality and aging potential, crafted from vineyards with unique characteristics that exceed the typical qualities of their village. Amongst the best-known wines are Le Montrachet, Batard-Montrachet, and Corton Charlemagne. Some Grands Crus make both red and white wines. Unlike the Premier Crus, the Grand Cru’s name always appears alone on the label, possibly accompanied by its Climat (Chablis Grand Cru has 7, and Corton 24).

Premier Cru (10-12% of production): These high-quality wines come from specific vineyard plots with favorable exposure at mid-slope, within a village, but just below Grand Cru status. Premier Cru and Grand Cru vineyards are mainly located at elevations between 250 and 300 meters (800 to 1,000 feet). The village Premier Cru appellations account for 11% of the vineyard. They surpass simple village appellations in quality and are often subject to stricter regulations, including notably lower production yields.

‘Village Wine (36-38% of production): Wines produced from vineyards within specific villages are named after the villages they come from and cultivated on Climats, where the ground (less fertile and thus more congenial for vines) starts to slope upwards, providing better drainage for vineyards. These wines are often of excellent quality and more affordable than Premier and Grand Crus. They are a group of village appellations (like Nuits-Saint-Georges, Givry, and Chablis) representing 39% of the vineyard. A ‘Village” appellation can extend over two or even more villages.

This is the case, for example, of Gevrey-Chambertin, whose appellation area includes that of Brochon, where the French authorities say the appellation starts. However, the wines of Chassagne and Puligny-Montrachet, although close neighbors differ significantly in terms of finesse and richness.

Regional Wines, a great introduction to Burgundy wines, are classed at the bottom of the qualitative pyramid. These cover 48% of the winegrowing area. These include Bourgogne Rouge, Bourgogne Blanc, Crémant de Bourgogne, Bourgogne Aligoté, Coteaux Bourguignons, Bourgogne Passe-Tout-Grain, and Bourgogne with specific geographic labels like Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune, Mâcon Village, or Mâcon with a village name, such as Mâcon La Roche-Vineuse. All are entry-level wines made from grapes grown over a larger area, typically on lower-lying or flat, fertile land.

Burgundy is widely viewed as the homeland of the concept of terroir, the idea that a wine is the product of a specific site, defined by its unique geology, topology, soil composition, and mesoclimate. Nowhere else in the wine world are such distinctions made between neighboring vines—tasting these differences in wines is part of the journey of learning about Burgundy.

‘Sense of place’ is probably the most commonly used term to distinguish terroir-driven wines, the sensory attributes of which are linked to the location where they are made. That’s when a wine’s characteristics and quality are primarily or exclusively due to its terroir: its geographical environment and inherent natural and human factors.

The International Organisation of Vine and Wine includes a cultural dimension in its definition of terroir:

‘A concept which refers to an area in which collective knowledge of the interactions between the identifiable physical and biological environment and applied viti vinicultural practices develops, providing distinctive characteristics for the products originating from this area.‘

Undoubtedly, Burgundy is the historical home of this cultural dimension, this application of collective knowledge: In Burgundy, it has been widely demonstrated how wine can differ in quality and style, even when the vine plots are just a few meters apart, are cultivated in the same way, and grapes are vinified in the same or similar way. Burgundy winemakers and critics say Burgundy wines provide evidence of the effect of terroir.

In Burgundy, terroir defines the region’s specific vineyard sites or plots of vines, known locally as Climats. There are a whopping number of 1,247 different climats, more than half of which (648) are classed as Premier Cru, all delimited according to their geological, hydrographic, and atmospheric characteristics and hierarchically classified under the Appellations d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) system.

Climats, marked and named over the centuries, are located on the slopes of the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune south of Dijon, the capital of Burgundy. Each Climat has specific natural conditions (geology and exposure) as well as vine types and has been shaped by human cultivation. Over time, they became acknowledged for the wine they produced. This cultural landscape includes two main areas: first, the vineyards and the surrounding production sites, such as the villages and the town of Beaune, which together showcase the business side of wine production. The second area includes the historic center of Dijon, which embodies the political and regulatory impetus that gave birth to the Climats.

These sites are an outstanding example of grape cultivation and wine production developed since the late Middle Ages from a winegrowing tradition dating back to Gallo-Roman times, more than 2,000 years ago, as attested by an ancient vine discovered in 2008 in Gevrey-Chambertin.

A Climat is usually smaller than a specific appellation. The name of a Grand Cru can be a Climat. In 2015, Burgundy’s Climats became listed within the UNESCO World Heritage as World Treasures of Humanity. This diverse landscape features ‘Clos,’ a plot of vines enclosed with dry-stone walls, one of the hallmarks of Burgundy vineyards. Constructed as far back as the Middle Ages, these walls were destined to protect the vines from the herds of animals that used to pass freely through the villages. Some of the ‘Clos’ are among the most reputed Climats, such as Clos de Tart, Clos de Bèze, and Clos des Lambrays.

The terms ‘Climat‘ and ‘lieu-dit‘ are often confused in the region; a single Climat can contain several lieux-dits, or a Climat may cover only part of a lieu-dit. However, Climat refers specifically to a winegrowing plot. In contrast, lieu-dit is a generic geographical term that refers to a historical name or place and may or may not be a vineyard. In principle, each Village, 1er Cru, or Grand Cru appellation encompasses one or more different climats. On the other hand, some rare climats, such as Les Maréchaudes in Aloxe-Corton, may be partly Grand Cru and partly Premier Cru. Similarly, Damodes is divided between a premier cru and an appellation village in Nuits Saint-Georges.

For more information on Climats, visit: Cité des Climats & Burgundy Wines Experiences

Many of the stone-enclosed vineyards also feature a Chateau, such as the prestigious Clos de Vougeaut, a Grand Cru Pinot Noir vineyard planted in the village of Vougeot, which takes its name from the River Vouge that runs through it. Some call this wine Vouge Rouge.

Clos de Vougeot may seem modest at 50.97 hectares, but it is the largest Grand Cru vineyard in the region, and its wall is the longest (3.2 km). Yet, in contrast to the vast open expanses of Languedoc and Bordeaux vineyards, Clos de Vougeaut reflects Burgundy’s highly fragmented nature; it may look like a single, coherent site, but actually, Clos de Vougeaut has more than 80 owners, most of whom make wine under their own name/brand.

Grand Vin de Bourgogne (Great Burgundy Wine) is written on bottle labels of Village, Premier Cru, and Grand Cru wines. Regional burgundy wines are labeled Vin de Bourgogne.

Unlike Premier Crus, the Grand Cru name always appears alone on the label, possibly accompanied by its Climat. The Premier Cru label is always attached to the village name and sometimes accompanied by the name of the Climat where the wine is produced: for example, Morey-Saint-Denis 1er cru Clos Sorbé, Meursault 1er cru Les Gouttes d’Or. When the wine is a blend of various 1er crus, it does not bear a Climat label. Until 2020, the Côte Mâconnaise had no 1er cru. It now boasts 22 in Pouilly-Fuissé. Understanding villages and their names helps to understand labels and Burgundy as a whole, which is no mean feat.

Curiously, most wine-producing villages on the Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune have a double name. At the end of the 19th century, the name of the most famous parcel was simply added to that of its village of origin. Vosne, for example, added the Climat de la Romanée, while Nuits chose its parcel of Saint-Georges and Chambolle the Musigny. As Puligny and Chassagne share the same Grand Cru, both communes have added Montrachet to their names. This was a way of promoting wine tourism ahead of its time and attracting lovers of great wines. A handful of villages, such as Meursault and Pommard, resisted this move. Allegedly, this was due to discrepancies over; you may have guessed it…terroir.

The vintage of a wine is particularly important in Burgundy, where the terroir and weather significantly impact wine production.

As Aubert de Villaine, owner of the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, once said:

“Winemakers are on the front line when it comes to observing what’s happening to the climate. The fluctuations we have today are more significant than at any time in history.“

No crop is as distinctly shaped by its climate and origin as grapes—particularly in Burgundy, where, according to the Burgundy wine board, the concept of terroir has reached its peak through centuries of study and careful observation. Faced with the climate crisis, Burgundy producers are changing the rootstocks of vines for ones more suited to higher temperatures. Extreme weather conditions such as excessive heat, rain, drought, or frost can cause problems and affect the quality and quantity of the wine.

Burgundy wines are mainly single grape varieties – every plot of land gives each vintage its unique personality and characteristics. In Bordeaux, wines are generally said to be more reliable in terms of aging, partly because they are made from blends of different grape varieties; better-performing grapes can prop up other lesser ones in any given year. Grape varieties grown in Bourgogne, such as the thin-skinned, finicky Pinot Noir, are particularly sensitive to weather conditions that can affect acidity levels and, therefore, the taste and balance of wine – too much sun can cause grapes to dry out and become raisins on the vine, resulting in bitter wines that are sometimes referred to as ‘flabby.’ On the other hand, a season that is too wet or cold can result in unripe grapes that are prone to disease or rot.

In the Chablis (Chardonnay) region to the north, hailstorms, and frosts can be devastating, so you might see small fires, candles, or oil burners lit overnight to keep the temperature up.

Climatic conditions affect the balance of wine produced; some vintages are better for immediate consumption, but they may not age well if the properties of the wine are unbalanced. Red Burgundy is generally light in color, intensely fragrant, medium-bodied wine with a fruity, elegant palate redolent of cherries, redcurrants, and raspberries with notable acidity and relatively low levels of tannins. As one moves up the quality pyramid, there is greater complexity, aromatic intensity, and a finer or richer texture on the palate. Frequently, in the best wines, there may be a kirsch-like or almondy note of a cherry kernel. As it ages, it develops earthy aromas the French call ‘sous-bois’ (forest floor), the wonderful amalgam of smells you take in walking through a wood in autumn: undergrowth, freshly turned earth, mushrooms, truffles, perhaps a whiff of smoke.

Burgundy village wines (red and white) are aged in bottle for at least two to five years. Premier Cru red Burgundy can benefit from at least seven to 12 years of bottle aging, and Chardonnay wines six to eight years. Red Grand Crus, like La Tache, have been known to reach their peak after 20-plus years in bottle.

Generally, Premier and Grand Cru wines age longer. Drinking them can depend on your subjective taste or preference for youthful energy in wines or notes of older profoundness. Pinot Noir has moderate tannin levels- a vital preservative that allows a wine to age for decades. In general, Premier/Grand Cru red and white Burgundies will develop and improve in bottle for up to a decade—sometimes longer—after their release. Some white wines like Meursault are typically approachable from the outset. Generally, the same drinking youthful wine rule applies to lighter red wine styles, like Beaujolais.

Increasingly sought after over the past 25 years throughout the world, Burgundy has attracted new markets, especially Asia, but with a relatively small amount of availability, compared with, say, Bordeaux, top Burgundy Grand and Premier are unaffordable for the vast majority of people. Pricing became open to all through the emergence of the internet, and there has been vast secondary market inflation on Burgundy wines – with Burgundy sold at much higher prices than the prices sold by producers. Significant demand and little supply have all prompted numerous fraud cases involving fake labels of top Burgundy wine.

There’s much still to unearth in Burgundy beyond the better-known wine names and villages. Getting to know the villages of Burgundy is one way to get to know producers, as Jasper Morris MW says – where decades ago there may have been several good producers in each village, there are now dozens of them, with producers over the past 20 years making better wines. Try to seek out and taste wines from lesser-known villages like Fixin – few have even heard of the place. For alternative, less expensive, white village wines, the Mâconnais is one area that has gained prominence in recent years for making complex Chardonnay.

Meanwhile, grape Aligoté is the in-vogue alternative to the expensive and, at times, unreliable Chardonnay. High in natural acidity, Aligoté’s was the traditional base for Kir, the Burgundian aperitif of dry white wine sweetened with creme de cassis. However, the increase in average temperatures is helping to ripen Aligoté more fully, unlocking the white grape’s potential for nuanced complexity, adding notes of acacia, herb, and nuts to simpler apple and lemon character. The Lafarge family in Volnay calls its old vine Aligoté’ Raisins Dorés’ in recognition of the deep gold color of their fruit when it is picked. Older plants yield small, rich, golden grapes, unlike the luminous green often seen from younger vines. Burgundy’s production may be small, but it’s incredibly diverse in terms of vineyards and production – try a Crémant de Bourgogne as a valid alternative to Champagne.

While several European wine regions are grubbing up vines due to falling wine consumption, Burgundy is renewing production in villages around Dijon, its capital city, a production area that had 1,600 hectares of vines up until the 19th century. With 50 of 200 hectares planted in recent years, producers have requested permission from the INAO, France’s appellation body, to create a new appellation called Bourgogne-Dijon, raising the prospect of a fresh, alternative supply of wine for Burgundy lovers.

Other than my own knowledge and experience, here are some references:

If you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a minimum two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.