Amphora Wine: Reviving an Ancient Tradition for the Modern Era

By: Barnaby Eales / Last updated: May 2, 2025

Introduction

What have the Romans ever done for us?’ is one of the key questions asked in the Monty Python comedy film The Life of Brian. For one thing, they transported wine across their empire in amphora clay pots.

Today, there’s a growing new wave of amphora wine production, with winemakers increasingly using clay pots to make pure expressions of round and concentrated fine wine – they also can play a role in preserving acidity in wine over time. Producers are learning more through studies and exchanging amphora wine experiences, including the magical new story (Keep reading to discover it below.) about what happened when bees became attracted to exposed grape must in amphora.

Historical Roots and Rediscovery

Origins: The oldest use of clay vessels is probably the Georgian Qvevri, which were buried underground (for temperature stability) – elsewhere, producers tend not to bury clay pots- at least 6,000 years ago. The Egyptians created clay pots, as shown in the tomb paintings. The Greeks and Phoenicians are also understood to have used clay pots in wine production. Clay pots were traditionally also used to make wine in Armenia. Amphora is a general term used today, but here are several clay pot terms according to origin: Pithai (Greek, Dolium(Italian), Tinaja (Spanish), and Qvevri (Georgian).

The Amphora Revival: The move to go back to using clay pots (terracotta is when the pots are fired)- or even Qvevri, has much to do with natural-wine makers, but it has now reached mainstream producers; amphorae can even be found in wine which traditionally favor oak-barrel aging. In Bordeaux, an increasing number of Grands Crus Classe producers are aging part of their wines in amphora. Amphora wine production has, in recent years, spread to South and North America and South Africa. This revival is spurring a greater and more diverse use (length of skin contact varies, as does aging) of clay pots to make wine.

Over the past 20 years, there’s been a revival of the use of amphora winemaking in Alentejo, a historical heartland of amphora winemaking stretching back to the Romans more than 2,000 years ago and further afield in Portugal. Much like endangered languages, the ancient art of amphora winemaking faced the threat of fading into obscurity. However, it has not only been revived but has also spread beyond its traditional roots to new regions and gained global appreciation.

Unique Characteristics and Advantages

Micro-Oxygenation for Tannin Softening: Clay pots are porous, allowing the micro-oxygenation of wines. They can play the same role as oak barrels but do not impart oaky flavors or tannins to wines. Clay pots are usually cheaper than designer concrete eggs, and traditionally shaped amphora with a narrow base result in more vibrant wine.

Natural Winemaking: Amphora wine production is championed by producers who wish to produce pure expressions of grape varieties, providing the essence of each grape’s aromatic profile. Although some producers add sulfur before bottling (to preserve and protect the wine), generally speaking, nothing is added regarding additives or winemaking processes.

Temperature Stability: Clay pots provide a natural cooling system through the endothermic process of evaporation and transpiration. Georgian Quevri pots are buried, as stable ground temperatures help the wine inside maintain an adequate temperature range during fermentation—a solution developed long before modern winemaking technology. The size and thickness of clay pots determine the temperatures inside them during wine production and aging.

‘Natural Battonage’ Lees Contact: An essential aspect for all amphorae production is the current that sets up in the clay pot; it keeps much of the fine lees in suspension, adding to a perception of balance over time. Some producers stir the lees to trigger fermentation. Grape musts can move around more freely, encouraging the extraction of flavors and structure.

Due to their shape, there is natural convection and movement of the lees, which means that battonage is not required. Settling, the crucial process where suspended solids sink to the bottom of a vessel while the wine rises to the top tends to occur naturally and efficiently in amphora, thanks to their unique design.

Timelessness:

“We can only use our barrels about six times, but our clay pots (tinajas in Spanish) last forever; with time they get a build of tartaric acid which leads to less microgeneration and the slowing of the winemaking process,”

says Matthew Stewart, a poet and the director of bottled wine production at producer Viñaoliva in Almendralejo, in Extremadura, Spain.

Notable Producers and Regions

Georgia / Qvevri

In 2013, Unesco recognized Qvevri winemaking as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list.

They are essentially inert vessels found throughout Georgia, especially in primary winemaking regions such as Kakheti and Kartli in the east and Imereti in the central west.

The winemaking process involves pressing the grapes and then pouring the juice, grape skins, stalks, and pips into the Qvevri, which is sealed and buried in the ground so that the wine can ferment for five to six months before being drunk the following spring. Producers include Twins Wine House, Mildiani Family Winery, Meskhishvili Family Winery, and Tezi Winery. Classic Qvevri orange or amber wines from Kakheti’s central producing region commonly use local varieties such as Rkatsiteli, Kisi, Khikhvi, and Mtsvane. Saperavi is used for the reds.

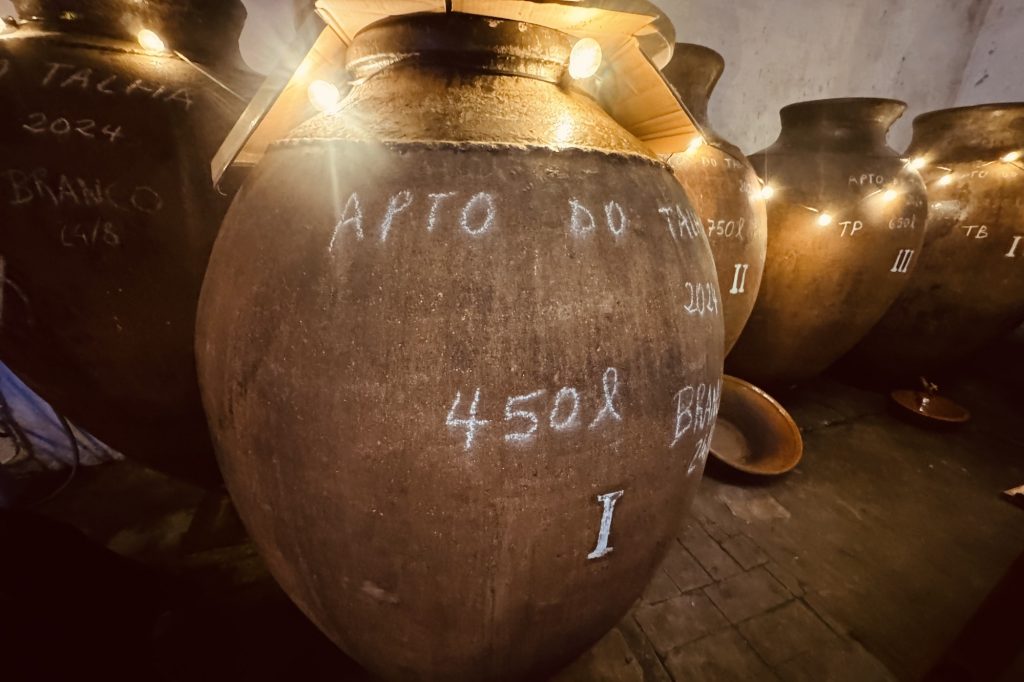

Portugal / Talha

Credits BE

Altentejo’s Vidigueira wine subregion is the heartland of Talha wines in Portugal. Still, amphorae wine production is increasingly popular across the country, in Lisbon, the Douro, and the northern Vinho Verde region.

Producer Barroca Da Malhada, for example, has put the Portuguese region of Beira Interior on the wine map by producing some of Europe’s finest, layered, and distinctive new Amphora wines.

Talha wine regained attention with the production of the red Talha wine Jupiter made at Alentejo producer Rocim in 2021—the wine became Portugal’s most expensive wine that year. Rocim’s winemaker and CEO, Pedro Ribeiro, is a stalwart of amphora production using different plots of vineyards and likes experimenting with different sizes of Talha.

Alentejo established the first Amphora wine classification, Vino de Talha DOC, in 2010. Rules stipulate that destemmed grapes are vinified in impermeable clay pots or talha; the wine is left on its skins until November 11th and is traditionally sealed under a layer of olive oil. In 2021, a PGI appellation was later created for Qvevri in Georgia.

In the villages surrounding Vidigueira, like Vila de Frades and Vila Alva, producers gather each November to taste and celebrate the new vintage of Talha wine, the local name of amphora wine. From November 11th onwards, for around a week, amphora enthusiasts go from cellar to cellar to celebrate the new vintage, when the first wines of the year are poured from the pots.

Locals burst into traditional Alentejo songs, which recount tales of love and working the fruits of land; it’s a fascinating culture where wine and traditional singing are all intrinsically linked. A singer sips his gold nectar and starts the singing dialogue, and others reply, and then all join in. This ‘call and respond’ singing culture, a forebearer of rap, including improvisation, is reminiscent of the ancient singing tradition of Kan ha Diskan in Brittany and the Bertsolaritza of the Basques.

In the village of Vila Alva, a new generation of locals have revived the culture to create XXVI Talhas, a producer home to an 18th-century Talha. One old cellar belonged to ‘Mestre Daniel,’ Daniel António Tabaquinho dos Santos, who produced Talha wine. The winery ceased production shortly after he died in 1985.

Still, the cellar was given a new lease of life in 2018 when Mestre Daniel’s grandchildren, Alda and Daniel, and their cousin Samuel and Ada’s childhood friend Ricardo Santos (the winemaker) founded XXVI Talhas. Meanwhile, Quinta da Pigarca in the village of Cuba refurbished its second winery in Vidigueira to accommodate wine tourism.

Since 2018, dozens of Producers worldwide have gathered to celebrate Amphora Wine Day, held at the modern Rocim winery in Cuba, in the Alentejo region of Portugal. This is a leading wine fair for clay pot enthusiasts and experts. Not only are producers increasingly using clay pots, but producers worldwide are also increasingly sharing and learning about their amphora, including how production methods can vary according to the grape varieties used.

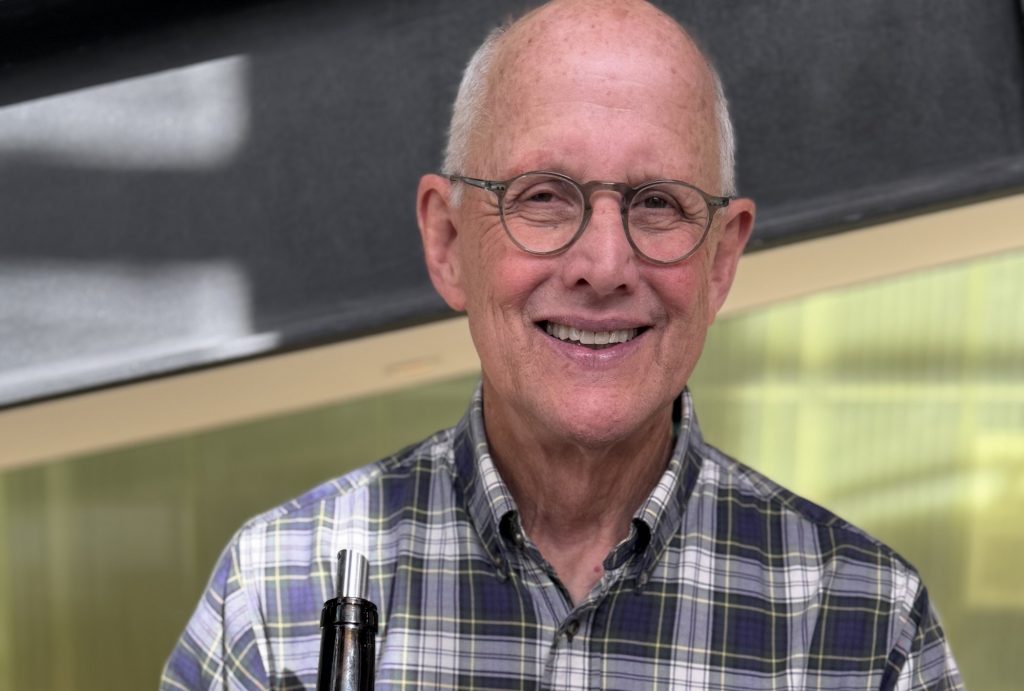

As Jon Engelskirger, winemaker at Tres Sabores winery in Napa Valley, who attended Amphora Wine Day in 2024, said:

“Travelling to Alentejo has provided context to many production points that I have observed here in Napa. Similarities and profound differences that all seem more at home with clay, as do I.“

Indeed, exchanging information and views in Alentejo has inspired Engelskirger and other producers to make new strides in production.

“In Alentejo, the varieties are distinctly different in their chemistry from what I’ve been working with. I have not yet worked with grapes where long maceration might benefit the sense of refinement of tannin; quite the opposite. I press at dryness, then return the wine immediately to the amphora. Due to a greater transfer of oxygen in the pots than in barrel, and even more so with my amphorae, because there is no pez [amphora lined at the top with beeswax and pine resin] involved, the effect is one of building the wine from it is a platform of high anthocyanin [pigments responsible for the color of red wine], not refinement of higher tannin.

“Next year, I will begin experimenting with Nero d’Avola, Tannat, and Tempranillo, which we also ferment here in small quantities. Perhaps I’ll work with them individually in three amphorae to better understand the effect of long maceration on each, then have fun with blending trials and return the blend to amphorae for bonding!“

Spain / Tinajas

Tinajas (Spanish amphorae) are strong, which means they are usually less porous and have less micro-oxygenation. The Tinajas Moreno Leon factory in Torrejoncillo near Caceres now makes Tinajas for producers around the world, including Catena in Argentina.

Loxarel, a leading Catalan and biodynamic wine producer has 27 amphorae in the Penedes wine region. It made the first amphorae wine in 2013 and is widely viewed as the producer that revived clay pot production in Catalonia, a region home to a high number of natural wine producers who favor amphorae use. Amphorae are also used in the Canary Islands and Extremadura.

Italy

Radikon in Fruili and Josko Gravner are credited as the instigators of modern ‘orange’ or amber winemaking. Amber-coloured white wine has been made in amphorae for centuries. Although Italian producers often use Dolium clay pots, Gravner was inspired by Georgia and had a garden of qveri pots buried at his estate in the northeast region of Collio Gravner. He made his first clay pot wines in 2001, spurring an Italian amphora wine production revival (see more here).

Terracotta Wine is an amphorae wine fair held every two years in Tuscany. Click here for more info.

United States

Andrew Beckham of Beckham estate in Oregon is known as the US’s first commercial producer of amphorae. However, one of the most magical stories of amphora use occurred during the sweltering summer of 2022, during the production of St Laurent red wines at the Tres Sabores winery in Napa Valley.

Winemaker Jon Engelskirger noticed bees from the estate’s hive next door had been attracted to the whole cluster and grape must of St Laurent red wine, settling in the shade on the open lids of 350 and 400-liter amphorae. (Lids are closed after fermentation.) Remarkably, it soon emerged that the bees had left bacteria on the whole cluster, and grapes must have naturally inoculated the malolactic fermentation of the wine.

Engelskirger explained to Cellar Tours:

“When the spontaneous wild yeast fermentation concluded, the new wine tasted as though it had completed malolactic. Testing at our local lab confirmed this. Further testing identified the malolactic bacteria to be Lactobacillus Plantarum, which is essentially found in the gut of a honeybee.

“The beekeeper who helps manage our hive confirmed that at high temperatures, plants close down against the heat, and bees are unable to access their nectar. They go looking for any source of sugar they can find. The St Laurent are the first red grapes picked each year, so they partied on that!

“I’ve learned that this malolactic bacterium works best as a co-ferment with yeast, preferably introduced before or concurrent with the onset of significant yeast activity. It doesn’t compete with yeast and doesn’t result in volatile acidity or Biogenic Amine production (histamine being one).“

The Tres Sabores winery wanted to make a red wine without excessive alcohol, fermented and aged in amphorae and bottles. It sourced St Laurent grapes – a variety related to Pinot Noir, which achieves ripens at low sugar levels to produce around 11% ABV – whereby yeast is not as stressed toward the end of fermentation.

Together with the role the bees played, Engelskirger was pleased with the outcome. Not only did the wine reach optimal ripeness and relatively low alcohol to ensure a crunchy, bright, balanced wine with concentrated flavors and textures, but Engelskirger also realized that clay pots keep fermenting temperatures at appropriate levels.

Engelskirger also said:

“Clay, with its thermal mass, along with our big nighttime temperature shift, largely due to the moderating influence of San Francisco Bay on both Napa and Sonoma Valleys, kept the fermenting temps much cooler in clay.“

Other notable Producers/ regions

- Chile/Argentina: At Vik Winery in Chile and Catena in Argentina

- France: With notable producers and prestigious estates like Bordeaux’s Grand Crus use amphorae to age a percentage of their wine.

- South Africa: Journey’s End and Kleine Zalze

Winemaking Process with Amphorae

Pic credit: Quinta do Montalto.

Wines fermented and aged in amphora are fresh and rounded, producing rich, concentrated flavors. In some cases, clay can preserve acidity levels naturally during aging. Talha clay pots in Alentejo are traditionally lined with ‘pez,’ beeswax, and pine resin for cleanliness and to limit oxygenation. Some producers use epoxy, a plastic seal inside, and coat the insides of pots with unwanted wine prior to using them for production.

Sealings reduce oxygen input and mitigate any losses from vessels. The temperature used to fire the clay to make amphorae can impact the levels of oxygen entering the pots. At Arvad, a fine wine producer in the Algarve, Bernard Cabral, one of Portugal’s leading oenologists, uses amphorae made in Northern Italy, fired at a very high temperature (1.200°C), ensuring the perfect sealing of clay; there is no need for resin or epoxy, as the clay is less porous. In Arvad’s case, wine is made in direct contact with the clay with its ‘terracotta’ composition, providing what Cabral says is a unique smooth texture on the palate.

Focusing on long-aging, Portuguese producer AVC Talha de Frades fermented and aged the wine in Talha until November and then transferred it to another Talha for around five months before aging the wine in bottle for one and four years before release.

Georgian producers tend to use whole bunch clusters, pips, and skins. Some producers prefer limiting skin contact and aging wine without skins and pips for further refinement. After fermentation, the liquid wine rises to the top in a process of natural filtration, with the wine mass falling to the bottom of the clay pot.

Cost and Maintenance: Amphorae are labor-intensive and fragile compared to barrels and tanks. Proper care and maintenance are essential to prevent cracking and ensure longevity. In the past, CO2 produced during fermentation caused amphorae to explode when the cap of mass rose to the top of the amphora.

Sustainability and Appeal: As consumer interest in sustainability grows, the amphora method aligns well with eco-conscious values (wood barrels involve cutting down trees), adding a historic yet relevant allure to the wines crafted.

Bright and refined history in the making: The Preservation of Culture

The future appears bright for Amphora production; producers worldwide are increasingly using clay pots in production – as well as any production benefits – and their use is about preserving history and culture. In a nod to the growing prominence of amphorae production, Portuguese producer AVC Talha de Frades has spread the word of Talha to Lisbon with the opening of a Talha wine-led restaurant (recommended by Michelin) called O Frade (pictured) and is now building a new modern Talha winery (set to open at the end of 2026) that will be located in Vila de Frades, next to the ruins of the Roman Villa of São Cucufate, one of the most important remains of Roman civilization in the Iberian Peninsula.

Pedro Ribeiro, winemaker and CEO of Alentejo producer Rocim, calls the combination of local grapes and clay ‘extreme terroir.’ The use of amphorae has much to do with romance, too; it’s early days in terms of science, and there’s still much to learn.

Ribeiro says:

“We are making wine from grapes from our estate and aging it in clay from here, so it’s an extreme terroir experience.

Although amphora use is a very old technique, there is still much to learn and understand about clay pots; not many scientific studies have been done, and we are now conducting research into the thickness levels of each amphora and how this affects winemaking.“

References

Other than my own knowledge and experience, here are some references:

More information

If you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a minimum two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.