Cinsault Grape Variety: From Workhorse to Revival

March 11, 2022

Cinsault is a red wine grape that is important in the Languedoc-Roussillon wine region of France because of its tolerance to high temperatures.

By: James lawrence / Last updated: February 3, 2025

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

The Iberian Peninsula offers a treasure trove of indigenous grape varieties and unique wine styles. Among the most exciting is Baga, the signature red grape of the Bairrada region in north-central Portugal. Think of it as the country’s answer to Nebbiolo – running the gamut from divine nectar to tannic dross. In its youth, poor-quality Baga can be as seductive as a plague of mosquitoes descending upon a tropical paradise; the grape’s naturally high levels of acid and tannin can overwhelm the palate, leaving a distinctly bitter taste in the mouth. Faced with an ocean of rank astringency in the winery, it is little wonder that many producers sidelined Baga in the 20th century, prioritizing easier and softer alternatives.

Read more about Portuguese Red Wine

Yet, Baga has found itself in great demand in recent years, adored by oenophiles who seek ample acidity and freshness from their red wines. Revitalized by the new generation of ambitious winegrowers, contemporary Baga is a world apart from the astringent plonk made in the 1980s by lazy cooperatives. Better site selection and sophisticated winemaking are creating a new wine style characterized by deep minerality and impressive length. Sommeliers have cottoned on – Baga is now an essential part of trendy wine lists in New York, London, and beyond. It is rapidly becoming one of Portugal’s most important viticultural exports. Let’s discover it.

Portugal is a proud seafaring nation with a longstanding viticultural tradition of growing varieties not found anywhere else in Western Europe. Baga is no exception to this rule. Unlike many grapes embedded into French and Spanish terroir, it is widely believed that Baga is indigenous to Portugal and has probably been used to make wine since pre-Roman times. Strong evidence supports this assumption; many different Baga clones are found in central Portugal, indicating that its genetic ancestors were indeed native to the country.

The name Baga translates as “berry” in English, a fitting term for these small red grapes with surprisingly thick skins. The variety finds a natural home in the Bairrada region, flanked by the Atlantic, which imbues the wines with an unmistakably saline freshness and verve. This provides a nice counterpart to the high levels of tannin and acid found in Baga’s skins – both a strength and weakness of the grape.

Indeed, there is no doubt that producing high-quality wine from Baga is not easy. The vines are prone to giving high yields, benefiting bulk growers and infuriating quality-focused estates. A great deal of time and energy must be spent managing the excessive growth, including constant pruning and green harvesting in the summer. Moreover, Baga ripens late in the season – another problem as coastal Portugal receives a great deal of rainfall in the early autumn. Therefore, to harvest grapes with good levels of phenolic maturity, the yield must be kept artificially low, and only the best bunches can be used.

However, old vines are a different matter altogether. They are arguably Bairrada’s most precious resource, yielding small aromatic and concentrated fruit bunches. Unfortunately, many centenarian plantings were ripped out in the early 21st century to favor more productive varieties. Fortunately, a lobbying group called Baga Friends has helped stop this practice, encouraging growers to respect their heritage.

Ultimately, though, success largely depends on the harvest date. Baga is resistant to downy mildew (an affliction common to inclement regions), yet it can quickly develop bunch rot if the weather turns nasty. As a result, certain producers tend to pick fairly early in the season, running the risk of excessive acid and harsh tannin. On balance, waiting until late September at least to allow the tannins to ripen is probably advisable. Otherwise, Baga is unlikely to ever shed its youthful toughness and austerity, even after ten years in bottle!

Baga is nothing if not versatile: it is used to make rosé, sparkling wine, and dry red styles in Portugal. Some growers employ a system of staggered harvesting, picking certain bunches earlier in the season to make delicious fizz. The grape’s high acidity lends to premium sparkling wine production, offering good structure and backbone. Although such wines are rarely exported, they are worth seeking out while on your Portuguese vacation.

Nevertheless, every critic would agree that red wines are Baga’s greatest offering to the wine trade. Unusually for Portugal, the grape is often marketed as a single-varietal label, although blends are also permitted under the Bairrada DO rules. The way Baga is handled in the winery has changed dramatically over the past 25 years.

Any visitor to Portugal in the late 1980s would find a charming, rustic scene. Shortly after the harvest, a team of enthusiastic workers would be treading grapes with their feet, crushing the berries to release the juice from the pulp. Afterward, a warm fermentation would occur with the stems in ancient concrete vats. Unfortunately, this is not a recipe for producing fruit-driven, approachable wines. The inclusion of tannin from the stems could tip the balance into fierce astringency, smothering the fruit for up to a decade. Occasionally, it would never emerge, forever hidden by the wine’s unforgiving structure. If Baga was ever going to appeal to modern palates, then a dramatic overhaul was needed.

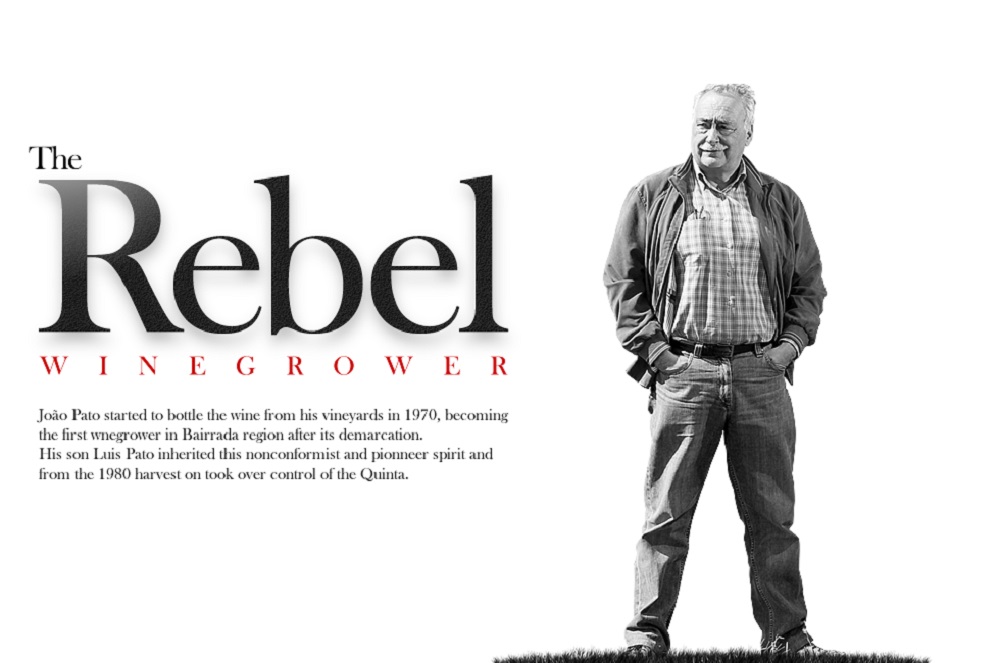

The solution was pioneered by Luis Pato, one of the great names of Bairrada’s wine renaissance. Pato embraced green harvesting and destemming the fruit using the latest equipment and techniques, fermentation in stainless steel, and maturation in new French barrique. Suddenly, Baga was palatable to oenophiles who like their reds soft and velvety, with ripe fruit and good acidity. But the traditionalists were not impressed. So they continue to make Baga in a historical way: wines for the long haul. The best of this firmament is undeniably glorious after 15 years in bottle. But, unfortunately, the worst never lose that unpleasant astringent grip.

Other winemakers advocate a third way. Dirk Niepoort, the owner of Quinta de Baixo, seeks an almost Burgundian finesse from Baga, with fruit-driven aromas set against that classical tannic structure. He achieves this via judicious site selection, old vines, partial destemming, and gentle extraction, aging the wines in either old wood or amphora. The result is a supremely elegant interpretation of the grape, neither soft nor aggressively tannic. Enjoyable in their youth, such wines will age into velvety complexity.

Baga is the flavor of the month in Bairrada and its eastern neighbor, Dão. After much trial and error, winemakers are producing very impressive reds from the grape – either blends or single-varietal labels. Both regions are between Lisbon and Oporto to the north, with Bairrada bisected by the highway linking Portugal’s two greatest cities. In Bairrada, the best wines come from clay-limestone slopes that flank the Atlantic, while Dão offers metamorphic granite and schist with some sandy topsoil; Baga will produce magnificent wine in a range of terroirs if the yield is adequately controlled. In the Serra da Estrela foothills in Dão, high-altitude vineyards have attracted a rash of investment from the owner in the Douro, intent on making fresh and precise reds.

A good example from either region competes for the title of Portugal’s finest red. The bouquet will be inviting and pungent, with cherry, blackcurrant, and blackberry notes. Crucially, the fruit will – or should – coexist with a typically powerful structure, with good acidity and firm, if ripe, tannins. With age, tertiary flavors of tar, tobacco, and aniseed will come into the foreground. Thanks to the pioneering efforts of men like Luis Pato and Dirk Niepoort, full confidence in the variety has been restored. The days of tired, monotone wines are largely over.

Yet despite this uplifting return to grace, producers remain divided over its future. Certain winemakers insist upon blending in varieties like Touriga Nacional, determined to make the wines as approachable as possible. Meanwhile, bottles labeled ‘Garrafeira’ maintain the traditional tannic style, albeit with more fruit concentration than was seen 30 years ago. In the end, Baga will always be a tough grape to grow and manage. Thanks to the ingenuity of Portugal’s iconoclasts, however, there is now a range of styles to please everyone.

If you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a mininium two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.