Pisa Travel Guide

More Than the Leaning Tower – A Cultural Capital of Tuscany

Globally famous for its iconic tower, there is far more to this cultural capital than the endlessly photographed Leaning Tower of Pisa. The city was once a maritime power to rival Genoa and Venice, a legacy that has endowed Pisa with a rich mosaic of cultural and hedonistic attractions. Education has fuelled the economy since the 1400s – students from across Italy compete for places in Pisa’s elite university. Meanwhile, visitors marvel at the vibrant cafe and gastronomic scene, balancing an enviable portfolio of Gothic churches, Renaissance piazzas, and Romanesque buildings with the sheer pleasure of sipping wine in one of Pisa’s many picturesque squares. While Pisa may not boast the fame of Florence, it stands as a source of regional pride in Tuscany.

Pisa’s history is a dramatic opera that opens with the wine-loving Etruscans around the 9th century BC. They formed the most powerful nation in pre-Roman Italy, building a great civilization across central Italy. Unfortunately, their neighbors increasingly cast an envious eye over the prosperity of Etruria – the Romans completed their conquest of Etruria in 265 BC. The Etruscans didn’t take kindly to Roman authority – they secretly allied with the Carthaginian ruler Hannibal to bring about the Romans’ defeat, which was ultimately unsuccessful.

But after the Roman conquest of central Italy, they took a more hands-off approach with the proud Etruscans, granting them citizenship in 88 BC to manage their affairs in the newly created province of Tuscia (Tuscany). Pisa subsequently became an important naval base – historians aren’t sure exactly when the settlement was founded – and a commercial port under Rome remained an important port for centuries. It was an essential base for Roman naval expeditions against rival powers in Italy and the Mediterranean.

Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, Tuscany experienced many centuries of turbulent upheaval. First came German emperor Theodoric, who was supplanted by the Byzantine emperor Justinian. The Lombards from northern Italy also controlled Pisa, but Charlemagne defeated them in 744. Politically, it became part of the duchy of Lucca in northwest Italy, although Vikings captured the settlement in the 9th century. Nevertheless, Pisa was granted the status of county center of Tuscia in 930.

Pisa’s golden age began late in the 10th century after recovering from the previous centuries’ political machinations. Pisa became an independent maritime republic and a formidable rival to the cities of Genoa and Venice. A century on, the Pisan fleet was sailing beyond the Mediterranean, helping to repel the Saracen invaders and trading with the Orient. At the peak of Pisa’s power (the 12th and 13th centuries), the rapidly expanding city controlled Corsica, Sardinia, and the Tuscan coast.

During this period, Pisa enjoyed a flourishing of new buildings endowed with a distinctive Pisan-Romanesque architectural style that emphasized the use of colored marble and subtle references to Andalucian architecture. Many of the most excellent examples were by the legendary father-and-son sculptural team of Nicola and Giovanni Pisano.

Unfortunately, Pisa’s fortunes started to decline towards the end of the 13th century. Genoa’s fleet devastatingly defeated Pisa at the battle of Meloria in 1284. The 14th century would be marked by economic collapse, plague, war, and tyranny throughout Tuscany. In the bubonic plague outbreak of 1348, approximately two-thirds of the population was lost in cities across Tuscany. The plague wiped out the entire hospital and monastery populations. Dark times, indeed.

However, in 1406, Pisa fell to Florence after much fighting between the rival powers. This was ultimately to the city’s benefit, as the Medicis – a powerful family of the Renaissance – encouraged great artistic, literary, and scientific endeavors and re-established Pisa’s university, where the city’s most famous son, Galileo Galilei, taught in the late 16th century. His story is a fascinating one. Galileo’s meticulous observations of the physical universe attracted the Church’s attention, which by the 16th century had a problematic relationship with the stars. Galileo’s findings that the earth revolved around the sun and not the other way around ruffled many religious feathers, including Paul III. Under the threat of torture, Galileo wrote that he might have overstated the case for the Copernican view of the universe. He was allowed to carry out his prison sentence under house arrest. But despite his troubled final years, Galileo’s groundbreaking work had massive repercussions for the scientific community and Western civilization.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw more political turmoil for the citizens of Pisa. Austrian Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa established her husband, Francis, as the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Subsequently, after the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte in France, he took over large swaths of Tuscany in 1799 during his violent campaigns across Europe. However, following Napoleon’s fall from grace in 1814, the Habsburg king Ferdinando III took over the title of the Grand Duke of Tuscany.

The 19th and 20th centuries were no less tumultuous. In 1861, Italy was united under one flag, although the early split between radicals and conservatives would define Tuscany’s future political landscape. Italy got more war than it bargained for in 1914 when WWI broke out. A young, prominent socialist firebrand named Benito Mussolini led Italy’s call to intervene in support of the Allies, leading to his expulsion from the socialist party. As a result, he formed the National Fascist Party, which took control of Italy before WWII. In 1922, the Fascists marched on Rome and staged a coup d’etat, installing Mussolini as prime minister.

The horrors of the Second World War brought much suffering to the citizens of Tuscany. In Pisa, only the Leaning Tower and Cathedral were spared from the Allied bombing campaigns. A still-unknown number of Italians were sent to death camps in Germany. A stone in front of Florence’s synagogue memorializes the 128 Jews from the city who died in these camps. Jews shared similar fates in Pisa, Siena, and other Tuscan towns.

Nevertheless, Pisa recovered from the horrors of WWII, emerging as the proud regional capital of northern Tuscany. Romanticized worldwide, Tuscany has impassioned more writers, artists, and tourists than any other European region. Yet what makes the birthplace of Gucci, Cavatelli, and the Vespa scooter so inspiring, so dolce (sweet)? In Pisa, you will find answers, but perhaps not where you expect. Of course, the Leaning Tower is a must-visit attraction, but Pisa’s authentic charm lies in its adherence to the fabled Dolce Vita. There is no better time of day or week than late Sunday afternoon to witness this in action – the entire city hums with families and couples taking a “passeggiata” (early-evening stroll). Take a gelato, sip wine, relax in one of the many beautiful piazzas, mooch, contemplate, and admire the sunset. This is Pisa’s La Dolce Vita – relishing the close of the day at an exceedingly relaxed pace.

-

Bistecca alla Fiorentina Gastronomy & Wine

Life is sweet for this privileged pocket of Italy, one of the country’s wealthiest enclaves that benefits from abundant fresh produce, world-class gastronomy, and sacred vineyards. Whether sinking your teeth into a bistecca alla Fiorentina (chargrilled T-bone steak), savoring Livorno fish strew, or devouring white truffles unearthed around San Miniato near Pisa, traveling in Tuscany is all about fine food and drink. A younger firmament of chefs, often having traveled abroad, continue to shake up the region’s food scene with innovative versions of traditional Tuscan dishes.

Nevertheless, for most Pisans, good food means remaining faithful to the region’s humble roots, using only fresh produce and eschewing fussy execution. Indeed, prime beef cuts were the domaine of the wealthy, and offal was the staple fare for most Tuscans. Tripe was simmered for hours with onions, carrots, and herbs to make lampredetto or with tomatoes and herbs to make trippa alla Fiorentina – two classics widely available in Pisa today. In the autumn, cinghiale (wild boar) will make a regular appearance on menus, often turned into salsicce di cinghiale (wild-boar sausages) or simmered with tomatoes, pepper, and herbs to create a rich and satisfying casserole. Tuscans are enthusiastic consumers of all manner of pork dishes – finocchiona (fennel-spiced sausage), prosciutto, and mortadella (a smooth-textured pork sausage speckled with cuves of white fat) are local highlights.

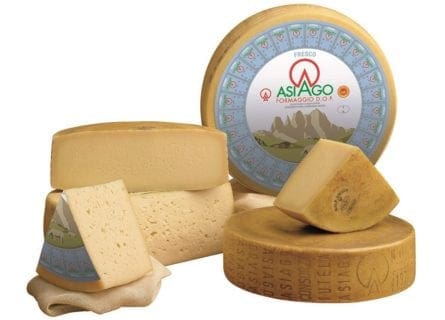

However, that is not to suggest that Pisans aren’t equally passionate about their fresh vegetables and surfeit of local non-meat produce. Pulses regularly appear on menus – minestra di Fagioli (bean soup) and minestra di pane (bread and bean soup) are delicious and hearty, the epitome of local Tuscan cooking with fuss and faff omitted. Tuscany’s lush landscape grows all manner of vegetables and herbs to perfection, including tomatoes, wild fennel, black celery, red onions, artichokes, zucchini flowers, black cabbage, and chard. The list is almost endless, as are the countless local recipes that fully use this plentiful bounty. Other Pisan specialties include fresh pecorino (sheep’s milk cheese), zuppe di cavolo (cabbage soup), pan ficato (fig cake), and castagnaccio (chestnut-flour cake enriched by nuts).

Meanwhile, oenophiles have long recognized Tuscany as a leading source of fine wine, with numerous appellations and sub-regions catering to every desire. Bolgheri, situated south of Pisa, is the source of two of Tuscany’s most famous wines – Ornellaia and Sassicaia. Bordeaux varieties are grown here in a remarkable terroir; the vineyard’s proximity to the Tyrrhenian Sea greatly impacts the microclimate, moderating temperatures significantly during the summer months, especially in the evenings. It creates a hybrid maritime-Mediterranean climate, aided by the altitude of the vines, spread out on rocky hillsides. Brunello di Montalcino, the product of Sangiovese grapes grown south of Siena, aged for two years in oak, will also appear on Pisa’s best wine lists. Intense and complex, with an ethereal fragrance, it’s ideal for game, wild boar, and roasts. Luckily, all great staples of the Tuscan kitchen!

Nearby Wine Regions

-

Tuscany's 3,000-year wine history has evolved from local secret to global fame, boasting renowned Sangiovese reds and complex Chardonnays. Read more

Tuscany's 3,000-year wine history has evolved from local secret to global fame, boasting renowned Sangiovese reds and complex Chardonnays. Read more

Highlights

-

Leaning Tower

One of Tuscany’s signature sights, the iconic Torre Pendente truly lives up the its billing, leaning 3.9 degrees off the vertical. The 56m-high tower took almost 200 years to build. Enjoying the view from the top is one of Italy’s obligatory experiences.

-

Duomo

Pisa’s magnificent 11th century Duomo, with its striking cladding of green and cream marble, was the blueprint for Romanesque churches throughout Tuscany. The elliptical dome, the first of its kind in Europe at the time, dates from 1380, and the gorgeous 24-carat gold decorations across the wooden ceiling is a legacy of Medici rule.

-

Museo Nazionale di San Matteo

This inspiring repository of medieval masterpieces sits in a 13th-century Benedictine convent on the Arno’s northern waterfront boulevard. The museum’s collection of paintings from the Tuscan school is astounding – don’t miss Fra’ Angelico’s Madonna of Humility.

-

Palazzo Blu

Facing the Arno is the magnificently restored 14th-century building with a striking dusty-blue facade. It houses Pisan works of art from the 14th to the 20th centuries. There is also an archeological area in the basement.

Recommended for you

More information

If you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a mininium two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.