Madeira Wine Region Guide

Discover the rich flavors and captivating beauty of Madeira, one sip at a time.

Last updated: June 10, 2025

Introduction

The iconic home of Portugal’s ‘other’ fortified wine holds a secret. On this subtropical paradise, situated off the coast of Morocco, a small (but growing) volume of exceptional still wine is made. That fact often surprises visitors who associate the island with rich and nutty fortified wines; the finest Madeiras can be aged for a century or more, developing complex flavors that defy words. Indeed, it vies with Port for the world’s greatest fortified wine title. Occasionally, vintages made in the 18th century will surface in the auction market. But, unfortunately, to sample such a rare piece of winemaking history is a privilege sadly reserved for the few.

Yet most consumers remain utterly aloof to the wines of Madeira – fortified styles fell out of fashion in the 1900s as oenophiles began to obsess over dry wines. As a result, the island’s leading merchants and growers have been forced to diversify their portfolios: dry white Verdelho is well worth seeking out. Aromatically expressive and beautifully fresh, it represents the new generation of Madeira wines. But traditionalists will not hear of it; they regard the production of fortified wines as sacrosanct. Plus, ça change.

History

Wine has been the principal export of the Madeira archipelago for over four centuries; the story of Madeira’s transformation from a rugged wilderness into one of Portugal’s leading vineyards has been told many times. Nevertheless, it is a charming tale! History records that three Portuguese explorers – João Gonçalves Zarco, Bartolomeu Perestrelo, and Tristão Vaz Teixeira – set foot on the island in 1419 at the settlement of Machico in the east. Either by accident or design, the trio subsequently set fire to the dense woods that gave the island its name. It is said that the fire burned for years, leaving the already fertile soil enriched with the ashes of an entire forest.

However, Madeira did not become widely associated with wine growing until the mid-17th century. The Portuguese were initially far more interested in the potential of neighboring Port Santo, a smaller island that benefited from a drier climate and sandy soils. The first settlers planted scores of Malvasia in Porto Santo while a burgeoning sugar cane industry was developing in Madeira. Unfortunately, overproduction and disease virtually wiped out this business by the end of the 1400s. And so the island’s investors went in search of another valuable crop.

Against their better judgment, growers began to plant Malvasia (Malmsey), Verdelho, Bual, and Sercial on the steep terraces of this spectacular island. But although Madeira’s volcanic terroir has few parallels in the Portuguese mainland, its Atlantic-influenced climate would struggle to ripen the berries in difficult years hence why sugar has long been a vital part of the ‘Madeira recipe,’ used to soften the often astringent wines of the island. Nevertheless, Portugal’s expanding overseas empire was about to place Madeira at the center of the global wine map.

Settlement of the American colonies meant increased traffic and trade; Funchal became the key Port in the Atlantic for westbound ships. With a need for fresh supplies, giant bottles of Madeira would be stored in the ship’s hold. Yet these potent wines performed three functions: Madeira was used as ballast (stabilizing material), an antidote to scurvy, and a post-dinner tipple in the officer’s mess. Fortified with a bucket (or two) of brandy, Madeira would slowly oxidize in the warm bowels of the ship, transformed during the long trips to Brazil. Most normal wines would have become rancid very quickly, and yet this concoction of sugar, wine, and alcohol was vastly improved by the sea voyage across the equator. The rest, as they say, is history: by the 1700s, Madeira had become the favorite wine of the American colonies. US President Thomas Jefferson is said to have imbibed several glasses after signing the American Declaration of Independence; George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams were no less enthusiastic acolytes of Madeira.

However, fate was to deal Madeira an almost fatal blow in the 19th century. A double disaster of oidium and phylloxera was compounded by falling global demand, exacerbated by the Russian Revolution and Prohibition in the early 1900s. For a time, it looked like Madeira would be consigned to the history books; vineyards were largely turned over to hybrids, while the classic varieties became rarities. Thankfully, the partial switch to dry styles has revived Madeira’s fortunes. But more importantly, the great merchant houses, not least Blandy’s and Henriques & Henriques, have kept this noble tradition alive.

Geography and terroir

The Carthaginians nicknamed this little archipelago the Enchanted Isles. Located about 640 kilometers off the coast of West Africa, Madeira is right in the path of sailing ships crossing the Atlantic. It is, however, very small: less than 55km across at the widest point. Its neighbors, Porto Santo, and the Desertas, are even smaller. But there is no denying the awesome beauty of Madeira, a subtropical island bathed in lush, verdant scenery. At the highest point (1,800 meters above sea level), visitors are afforded incredible views of the island’s precariously steep vine terraces, interspersed with crops and little flower gardens. Much like the Douro, vines are often cultivated in arbors (a vertical structure that provides shade), making room for other crops underneath. Meanwhile, irrigation channels distribute water from the peaks to the vines.

Yet wine growing in Madeira is far from easy. Although the island is endowed with igneous soils rich in minerals, summer humidity greatly increases the risk of fungal diseases, particularly oidium, and rot at harvest time. Such is the reality of cultivating vines in a maritime climate, with all the inevitable challenges; rain is frequent, especially on the north coast, which is unprotected from the Atlantic storms. Working these vineyards is undoubtedly not for the fainthearted.

Winemaking and regional classifications

Producing the finest Madeira is an art form.The techniques and approaches unique to the island have been perfected over the centuries; Madeira is no longer matured in cargo ships during long, hot sea voyages, regrettably.

Instead, the fermented base wines are placed into stainless steel tanks equipped with heated pipes. You might describe what happens next as a (gentle) ordeal by fire. The wine is warmed to about 45 °Celsius, replicating the tropical heat of cargo holds in the 1700s. This process takes approximately three months, although certain producers continue to heat their wines naturally, using sun-drenched lofts and then wine lodges. However, it is far more cost-effective to use the estufagem method. Nevertheless, it is important not to overheat the wine. Poor Madeira has a burnt sugar taste that obliterates the fruit: an overheated estufa is the usual culprit.

Today, entry-level Madeira wines are blended relatively soon after the heating process. These branded labels are both reliable and utterly forgettable. At the other end of the scale, the finest Madeiras are aged in wood for many years, a process known as canteiro, after the racks on which barrels are stacked. The crème de crème will have been matured for at least 50 years – occasionally longer. Interestingly, Madeira producers were historically committed to the solera method of blending different vintages to achieve a consistent product.

However, most premium bottlings are based on wines of a single vintage and variety. Colheita Madeiras are made from the produce of a single vintage, bottled after spending five years in barrel. They currently represent the best value. Meanwhile, the classifications Reserve, Special Reserve, and Extra Reserve guarantee that the wine has been aged for five, ten, and fifteen years, respectively. Vintages are matured for a minimum of 20 years prior to their release.

Facts & Figures

Key wine styles

- Fortified and table wines

Appellation structure

- Madeira DOC (Denominação de Origem Controlada)

Hectares under vine

- 500 hectares

Average annual production

- 3.1 million liters in 2022

Approximate number of producers (not including growers)

- 7

The lowdown

Whenever the future of a troubled category like Madeira is discussed, exaggeration and hyperbole usually follow. You’ll find this tendency on both sides of the debate: those who proclaim that “Madeira is practically extinct” are grossly overstating their case; according to Humberto Jardim, the owner of leading shipper Henriques & Henriques, “the opening of economies, the relaxation of the protective measures allows us to conclude that we have returned to the normality of what was the usual consumption of Madeira wine in the traditional markets.”

He continues: “2021 and 2022 were years of sharp growth in Madeira wine sales with around +32%, and +8.4% of respective sales increase each year. In addition, the first quarter of 2023 shows a growth of 7,09% on sales being the US the first market.” On the other hand, aficionados of fortified wine often deliver an (overly) optimistic appraisal of Madeira’s future. The truth, as ever, lies somewhere in the middle.

One thing is certain: Madeira does have its fair share of problems. The production costs are extremely high, partially due to the island’s geographical isolation. Long-aged styles are glorious; however, the producer isn’t receiving any revenue while bottles languish in cellars. And we cannot pretend, of course, that Madeira is the height of fashion. Yet the fire will continue to burn, provided that a (relatively) small number of collectors continue to seek out older vintages of this venerable wine style. Madeira has a reason to exist as long as their interest is maintained. Moreover, the small volume of dry whites now made on the island offers a valuable income stream. Nevertheless, the struggle to survive continues.

Part of the problem is that Madeira is not easy to understand. It is often presented as a homogeneous category – nothing could be further from the truth. Neither is all Madeira sweet. Today, bottles are labeled according to age (3, 5, 10, and 15 years – 20 for vintage) and style (dry, medium, and rich). As in Port production, the latter is generally determined by the exact point at which the addition of spirit halts the fermentation. However, there is another helpful purchasing cue: grape varieties are often associated with a particular level of sweetness. Verdelho, for example, is made less sweet than Bual; Sercial Madeira is the driest, most refreshing wine produced on the island. The grapes are cultivated in Madeira’s highest vineyards and harvested late in the season. As a result, it is light, sharp, and fragrant – a rival to Fino Sherry as the ultimate aperitif.

Meanwhile, vintage expressions seem to last forever. The finest wines spend a century undergoing slow oxidation in wood, or glass demijohns, before being sold. The older it is, the better it is – an opened bottle of vintage Madeira will keep its freshness for many months, even years. That alone makes the category worth fighting for.

Key Grape Varietals

-

Bual

Bual, also known as Boal, is a grape variety primarily grown on the island of Madeira. It is highly valued for its ability to produce rich, full-bodied wines with a unique nutty and caramel-like flavor.

-

Malmsey (Malvasia)

Malmsey, also known as Malvasia, is a sweet grape variety that produces some of the finest fortified wines in Madeira. Its luscious, honeyed flavors and aromas of caramel and nuts make it a popular choice among wine lovers.

-

Sercial (Cerceal)

Sercial is a grape variety grown in Madeira, producing dry, light-bodied wines with high acidity and notes of citrus, almond, and spice. It is a versatile grape that can be enjoyed on its own or paired with food.

-

Verdelho

Uncover the history and unique characteristics of Verdelho, a lesser-known grape variety used to make fortified wines.

Find out more -

Tinta Negra Mole

Tinta Negra Mole: a versatile grape used in a range of Madeira wines, favored for its robust and fruity character.

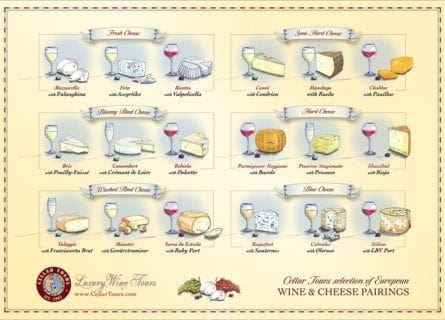

Madeira gastronomy

It is not difficult to find good food in Madeira. Its inhabitants are obsessed with dining out, while local chefs benefit from an almost endless bounty of fresh Atlantic seafood caught daily. There is an abundance of Madeira’s most iconic fish, black scabbard (Espada), often served with passion fruit and banns sauce – better than it sounds! Espetada is another highlight: beef skewers slowly cooked over charcoal. The Cozido Madeirense is also incredibly popular, a concoction of salted pork, spicy sausages, and sweet potatoes cooked over a wood fire. Enjoy it with couscous and a chilled glass of Verdelho. Perfection indeed

Further Reading: Discover More Related Blog Content

More information

If you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a minimum two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.